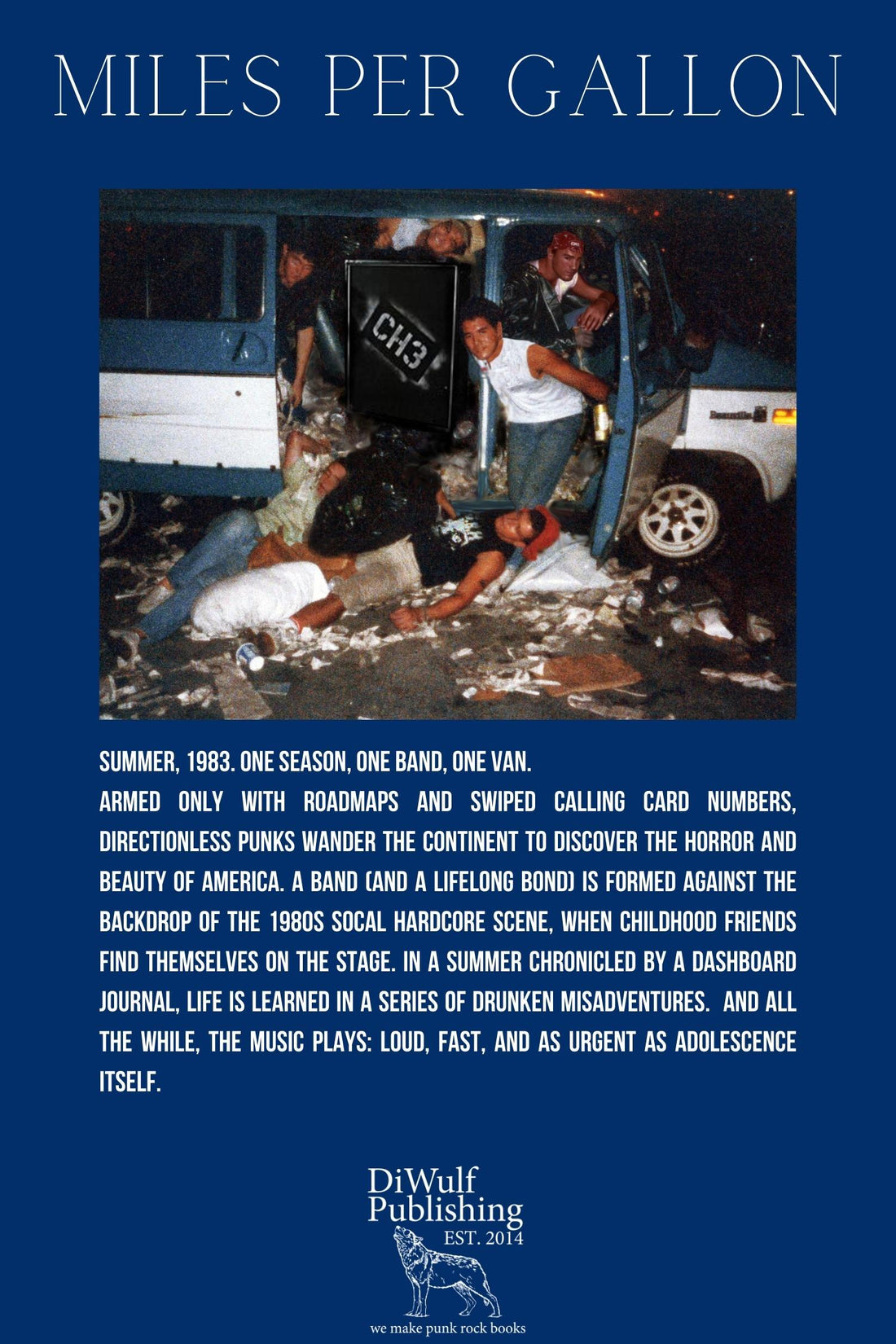

The following is an excerpt from Mike Magrann's CH3 book, Miles Per Gallon

Like most Japanese Americans of the Nisei generation, my mom’s life was bisected by the time before and after the internment camp.

My grandmother, Bachan, was a girl named Kinuye who came over from Hawaii as a picture bride to my grandfather, Makoto.

Makoto was a serious man with huge ears and heavy jowls, peering out from the faded photos simian and suspicious.

They married, then ran a Chinese restaurant in San Francisco, rumored as a safe house for Yakuza members hiding out in the States.

I picture Bachan back in the kitchen, braising chicken feet in a neon orange sauce.

Upstairs, my grandpop adjusts a table light to illuminate the bleeding man lying across their dining table.

He prepares to stitch a switchblade wound shut with 4lb. test fishing line.

He chews at his tongue while he works, struggling to keep the delicate lines of an Oni Mask tattoo matched on a bleeding gangster’s backpiece.

They started a family, a girl then two boys.

My mom, Teruko, then Uncle Ich and Uncle Sets.

They left the greasy floors and bloodied gangsters behind and moved to Delano, a farm hub north of Bakersfield.

Family fables smoothed by time like a submerged rock rounded by unrelenting currents.

The nasty bits of shame dulled, crimes rewritten as duty or forgotten altogether.

Bachan heard the knocking, only to find it wasn’t knuckles upon door she heard, but an 11 x 17 placard being nailed into the clapboard siding of their home.

INSTRUCTIONS TO ALL MEMBERS OF JAPANESE ANCESTORY it began, the print scrolling smaller as it continued down, the words shrinking as their intentions grew more evil.

Bachan stood on tip-toe and looked closely at the words, her nose almost touching the paper.

Sounding out each English word aloud in a whisper, she surely misunderstood the instructions.

By the time my mom came out to the porch and read it for her, their life was already slipping away.

They were told to take only what they could carry, leaving behind their furniture and home, and report to a bus station.

Go somewhere else.

Bachan fretted over the weight of the tetsubin, if she could bring her bowls and cups. Mom assured her they would carry the iron teapot for her, though the lacquered rice bowls would have to stay.

Grandpa took a lantern with him to the vineyards that night, his Japanese ceremonial swords bundled in burlap like a burial shroud. He dug a hole, then dropped the swords into the earth, taking stock of the grave from every vantage in the futile hope he would someday be back to retrieve them.

He smoothed the dirt beside the grapevines he had tended just that morning but would never see harvested, their fruit still green and bitter.

The night before they were to report to the bus my mother lay awake.

She sat at the sound of muffled voices outside, and then raised a corner of the window shade by her bed.

Out in the street were two battered trucks, men standing in a tight circle.

Smoking, spitting.

The glowing red tips of their inhaled cigarettes floating like fireflies, their weathered faces illuminated briefly by match strike.

Mom said it was the Okies, waiting to come in when they left.

To squat in the vacated home, go through the closets and sniff at the strange pantry.

Shreds of dried seaweed are tasted then spit onto grandma’s immaculate kitchen floor.

By the time mom and her family were riding the bus to Santa Anita racetrack, the house is already cleared of clothes and hardware.

When they finally lay down to sleep in a horse stable that night, sharing with another family the space usually reserved for one thoroughbred gelding, dusty overalls sit upon their couch back in Delano.

Everclear alcohol splashed into Bachan’s prized lacquered teacups, the fine paint already weeping.

But my mom, telling the story again after we pestered her to relive it again, she never really blamed those people coming in and taking their things.

They were just another tribe fucked over and set to wander, though saved the indignity of barbed wire by color of skin and crease of eyelid.

When my mom’s family got out of camp, they came back west due to grandpa’s health.

The humidity never left Makoto’s lungs; the bumps left by mosquito bite seemed to never stop itching.

The family slowly made their way back west, stopping at readjustment camps along the way.

My mother took secretarial classes by day, developing a calligraphic handwriting that would forever make forging her name an impossibility.

She took a job at an egg processing plant in East LA and took her seat among the other Japanese women hired for their supposed prowess at candling eggs.

She spent her shift examining eggs by flame to determine if a developing embryo lurked within its shell, a life stubbornly intent on spoiling breakfast.

My father drove trucks for the same egg outfit. He took shifts after optometry classes, although he already knew he would not be satisfied with tending to just the eyeball and had already set his sight on medical school and becoming a General Practice MD.

As he huddled over stripped cadavers in the lab, his gaze wandered.

From the eyeball down to the body, from jaundiced sclera to the hematoma purpling the corpse’s torso, correctly diagnosing advanced cirrhosis.

As he drove the truck at night, he wondered at the greater mysteries held within chest cavities and intestines.

The eggs in the truck bed shuddered gently with each downshifted gear, each deemed safe for consumption by my mother’s almond shaped eyes, enchanted by candlelight.

They met, dated, saw plans for a daring future.

My brother John already nestled in her womb, an embryo yet undetected by my parents or candlelight, when they took a long night drive to Las Vegas to wed.

They were turned away, of course, the Irish sailor and the Japanese war criminal denied license or interracial ceremony in 1955.

Reaching the border by dawn, they married in Tijuana and were back in LA that night.

They spent their first married night together at my grandparents’ house in Boyle Heights.

They lay together, thinking of the future they’d instigated, regret and hope threading through their dreams.

Just before dawn they hear Bachan rise to fill the iron teapot.

And then they can hear Makoto in the next room, scratching at the phantom mosquito bites on his arms.